The Poetry of Land Rights: Down Under with Robert Bly

By John Stokes

(This was originally published as a chapter in Walking Swiftly: Writings and Images on the Occasion of Robert Bly’s 65th Birthday, edited by Thomas Smith ©1992, Ally Press)

FOR ABOUT A WEEK in 1978, I helped Robert Bly and poets from many different countries to meet the Aboriginal Australians during Writers’ Week of the Adelaide Festival of Arts in South Australia. In addition to his time with urban and tribal students at the Aboriginal Community College where I was working, Bly also took part in a large land rights march and rally with hundreds of central desert Pitjantjatjara people. These are a few memories from that time.

For Robert

“You don’t belong in here!”

Those were Robert Bly’s words to me as he stood in front of my desk at the Beacon Press in Boston. My boss, the senior editor, and I were preparing The Kabir Book for publication, and Robert had come for one of his rare visits. As he shook my hand, he continued, “You belong out here with us.”

Taking him at his word, I began to tag along when he came to town, attending the Great Mother Festivals of 1976 and ’77, sitting in on college campus readings and talks, meeting Etheridge, Gioia, Saul… and “all those nice American boys who smell of soap, love their mother and their girlfriend and would never start a nuclear war.” Bly was speaking at the time of the great need in America for grounding, of the weak rope over the chasm between the unconscious and the conscious, of the “infantilization of America,” and of the need to not use acquired language like “collective unconscious,” but to let our own psyches rise and slowly devour those terms in order to make them personal and original. Answering the call of a great snake deep within my own psyche, I left cold Boston in late 1977 and moved to Adelaide, South Australia.

Australia, the southern land. Land of the Rainbow Serpent. When Gondwanaland, the original land mass, broke apart into seven pieces, the great Rainbow Serpent coiled beneath also broke seven times. A portion still sleeps beneath each great land mass. Aboriginal Australians continue to remember this long-ago event. Forty-thousand years of Dreaming, the people singing and dancing the land. “White people sometimes think we make up all these sacred sites. We didn’t make ‘em. God made ‘em. We just found ‘em and knew they were sacred.”

One day in a pub, I heard a low droning growl and turned toward the sound to see a black man on television painted white, cockatoo feathers in his hair, cheeks puffed as he blew into a long log. As I watched, an Aussie standing next to me turned to the TV and laughed, “Bloody Abo.” Setting my pint down on the bar, I headed out the door toward the source of that sound. Looking in the phone book under “A” for Aborigine, I found a listing for an Aboriginal Community College. The world being a funny place, within a month of my first visit, I found myself teaching country western guitar to adult urban and tribal Aborigines from all around Australia at the college. “Okie from Mootwingie.” A secretive tribal man from the Kimberleys named Michaelangelo for his painting abilities noticed my attraction to the didjeridu—the log I had seen the man on TV playing –- and began to sit with me in a corner of the students’ Common Room each day. With my hand touching his throat as he played, I learned the breathing and mouth sounds used to make different rhythms. Dadeeron Dadeeoron. Didjemro didjemro didjemro. Like the Hanged Man in the Tarot deck, I began my education in learning to see the world upside down.

“Like looking at the back of your head without a mirror” was how I used to describe being in Australia. At that time the Community College was located in a run-down mansion in a flash part of North Adelaide, just beside the four-star Oberoi Hotel. The proximity of so many black Australians to wealthy overseas visitors proved to be a constant source of embarrassment to the hotel management, eliciting many difficult questions from startled guests. Some warm days I would sit outside with classes on the grass, looking at these two buildings which somehow seemed to epitomize the cultural chasm between the Aboriginal people and the new Australians. The distance from one door to the other was about twenty-five yards – or forty thousand years, depending on how you walked.

We are fighting a big fight for the right to be Aboriginal in Australia. Our bodies must keep doing the dances and living in the bush… These are the things we need to help us keep the head and body alive until we are given back our land and the land can make us whole again. We need the land to be Aboriginal in our minds. Without it, we will die.

– An elder, now deceased, from Mornington Island

Secret rainfall and hidden canyon springs can swell a river to overflow. In the spring of 1978, two streams of people made their way in to Adelaide. As Robert and other writers and artists began to arrive at the Oberoi, where they would camp during the Adelaide Festival of Arts, the council executive of the Pitjantjatjara people, a large tribal language group from the central desert, drove into town for land rights talks with the state government. Only a month before, two hundred Pitjantjatjara elders had camped in town on the Victorian raceway for an unprecedented “public” tribal meeting, hoping to show non-Aboriginals the careful, patient manner in which they make their collective decisions. With imminent mining leases on and near sacred sites, the people had come once again for a big land rights rally. Understanding that this might be their last chance, these people who had survived the last two hundred years in remote silence had decided to change their strategy. “Help will come from outside,” they knew. “We will be the folk heroes of tomorrow’s history books. We have been talking, but no one here has been listening.”

Robert and I met up at the Oberoi shortly after his arrival, laughing at this strange scene we had chosen for our next meeting. Later that night at a “get-to-know-you” dinner we met many of the other writers: China’s Yang Xianyi, Yu Lin, and Wang Zualiang, Chinua Achebe from Nigeria, Darmanto Jatman of Java, Kazuko Shiraishi from Japan, Professor P. Lal, poet and editor from Calcutta, as well as Joan Aitkin and Elliot Anderson from the United States. Peter Brook’s international theater company flew in from Paris for a series of plays including Ik, Ubu, and a filmed performance with tribal Aborigines. Robert agreed with me that a poetry reading for the Aborigines was a good idea, so I began to recruit the interested poets. “Would you like to meet the people who really ‘own’ Australia?”

Poets and singers are the people who remember what everyone needs to know. Changing little over thousands of years, the poet’s role has been to sing from the earth, from the peoples’ heart, from the heart of the community, reminding everyone of the origins of things, of the land, of words, of the human beings. As Uluru meets Manhattan, as the great serpent curls around to bite its own tail, healing itself with its own poison, the task of remembering means going back to the old stories, recovering the symbols, recreating the myths, and rebuilding mythic mazeways. Deep in thought as we walked back from a writers’ party one afternoon, Robert sat quickly on a low stone wall.

“It must be very difficult to be a writer in this country. They see all the value in a thin strip that goes around the coast and the whole interior as nothing but a wasteland inhabited by a few scrawny dark figures. The Dead Center.”

The more we thought about it, the funnier it seemed. “But the Dead Center is really the Living Heart,” we joked. And the Outback is really Infront.

Robert crossed the chasm to the Community College many times. While meeting with the students, amusing them with imitations of Kali, fangs dripping, necklace of skulls, one asked him “‘Teeth Mother Naked at last?’ What does that mean?” One afternoon, dispensing with “Christian nicknames,” the students introduced themselves by giving the name of their home country or community—Pipalyatjara, Mimili, Kununnurra, Amata, Point Pearce. Adelaide itself was once called Tandanya—place of the great red kangaroo—by the Kaurna people. Kazuko Shiraishi and Darmanto often joined us for these informal sessions, everyone sharing their cultural ways. For the Unlucky Australians the problem is not a lack of grounding, it is lack of ground. The sacred land, cared for by their people since the beginning of time, fed by the blood of countless generations of ancestors now stolen and parceled out. Massacres, poison, epidemics, assimilation, mining. “If they gave us back the land, I reckon the cities would nearly empty out of our people.”

“Strange that there are no Aboriginals here today,” Robert noted to the audience at a panel discussion downtown entitled Myth, Symbol, and Fable. “Some of the best storytellers in the world.” As the discussion turned to “good” and “bad” myths, bad myths being those which were perpetrated to persecute others, a voice from the audience stated that all myths were bad and that only by destroying all myth could Australia progress. To this Bly responded, “Sounds to me like that old American saying- ‘the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” When he mentioned that we had gone to see the movie, Picnic at Hanging Rock, the audience was anxious to know what Robert thought had happened to all those pleasant young schoolgirls who disappeared in the movie.

‘Do you know why those girls all disappeared at the rock? Because no one will acknowledge that that rock is Aboriginal country. And until someone does, all your little girls are going to disappear. We’ve already had it happen in America. First, they become black swans, and then do you know what happens? They become B-52s.”

Wednesday morning at the college, the Common Room was filled with students and their friends, lying on the floor or sitting around the room beneath bark paintings, woven mats, and other implements of traditional life. Chinua Achebe’s hushed whisper opened the reading with passages from his book Things Fall Apart. Robert tuned his dulcimer, telling the Aborigines, “This is an American instrument, but no one knows where it came from. It might be Icelandic. Or African. “Who knows?” After a few Kabir poems with the dulcimer, he prefaced a story: “An interesting thing is happening in the United States, We’re going back and instead of writing all new words we’re looking at fairy tales of Europe from say three hundred to four hundred years ago. And we’re retelling those stories to our children and to adults because there’s a lot in those stories we haven’t noticed.”

Kazuko read animal poems in her samurai movie voice and Darmanto danced and sang several kalatida – the traditional songs of Java. Maureen Watson, noted Aboriginal storyteller, joined us, as well as K. C. Das from India and Faye Zwickey from West Australia. One of the Aborigines later told me, “That friend of yours was just like one of our old songmen, the way he made the pain disappear with his words. You know, sometimes, the best thing you can do for us is just to make us laugh. It helps us to go on.”

After the reading, Robert came over. He seemed upset. “John, I have to tell you something. Don’t be angry with me. Who was that man sitting under the television set?” One of the students had sat through the reading on the lower shelf of the TV stand we used to wheel the set from room to room. He had dark black skin, a high forehead, and broad Aboriginal features. I told Robert his name. “Well, when the reading started,” Robert continued, “I couldn’t help looking at him because he was the strangest human being I had ever seen. But by the end of the reading, I realized he was the most beautiful human being I had ever seen. And I’d like to give him something.”

I spoke with the other teachers and found that this student could not read English at all. His grasp of English grammar was “A, B, C… shit, what’s the next one?” Great, I thought, since he can’t read Robert could give him a book that his teacher could use as a primer. Robert wrote out the inscription, “For Peter…” The book – This Tree Will Be Here for a Thousand Years.

Later that evening, we attended a talk by Professor Lal, who continued a theme he had developed in other talks on cultural identity- compassionate love. During the trouble in Bangladesh, he pointed out, millions of refugees had poured into Calcutta, swelling that city’s population far beyond the saturation point. Yet, for nearly six months, those millions were cared for and fed by people whose situation was a little better than those they helped. I wondered to myself what the history of Australia- and for that matter, North and South America- would have been like had the same compassion been practiced by the Europeans in their initial and subsequent meetings with the native peoples they encountered when the happened upon these vast populated continents. In his book, The Unlucky Australians, Frank Hardy writes that if Australia is the “Lucky Country,” then the Aboriginal Australians must be the unluckiest people of all. In the forward to that book, historian Donald Horned writes: “To be an Australian is, in part, to be an Aborigine. The Aborigines are part of our Australian-ness, part of ourselves as a nation. To treat them like dogs is, to that extent, to treat ourselves as a nation of dogs… To the extent that we still tolerate the de-humanisation of Aborigines, we take some of the humanity out of ourselves.”

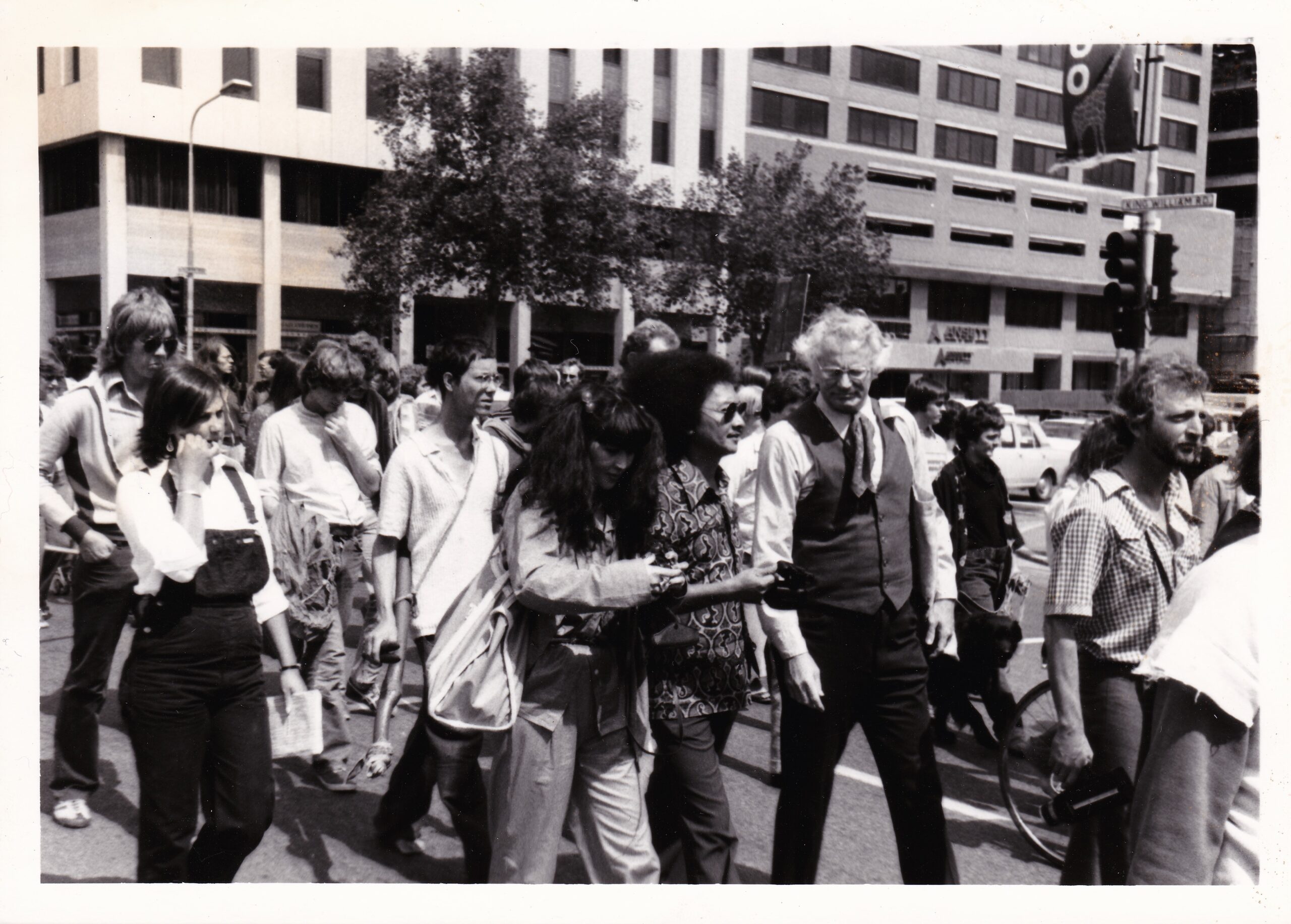

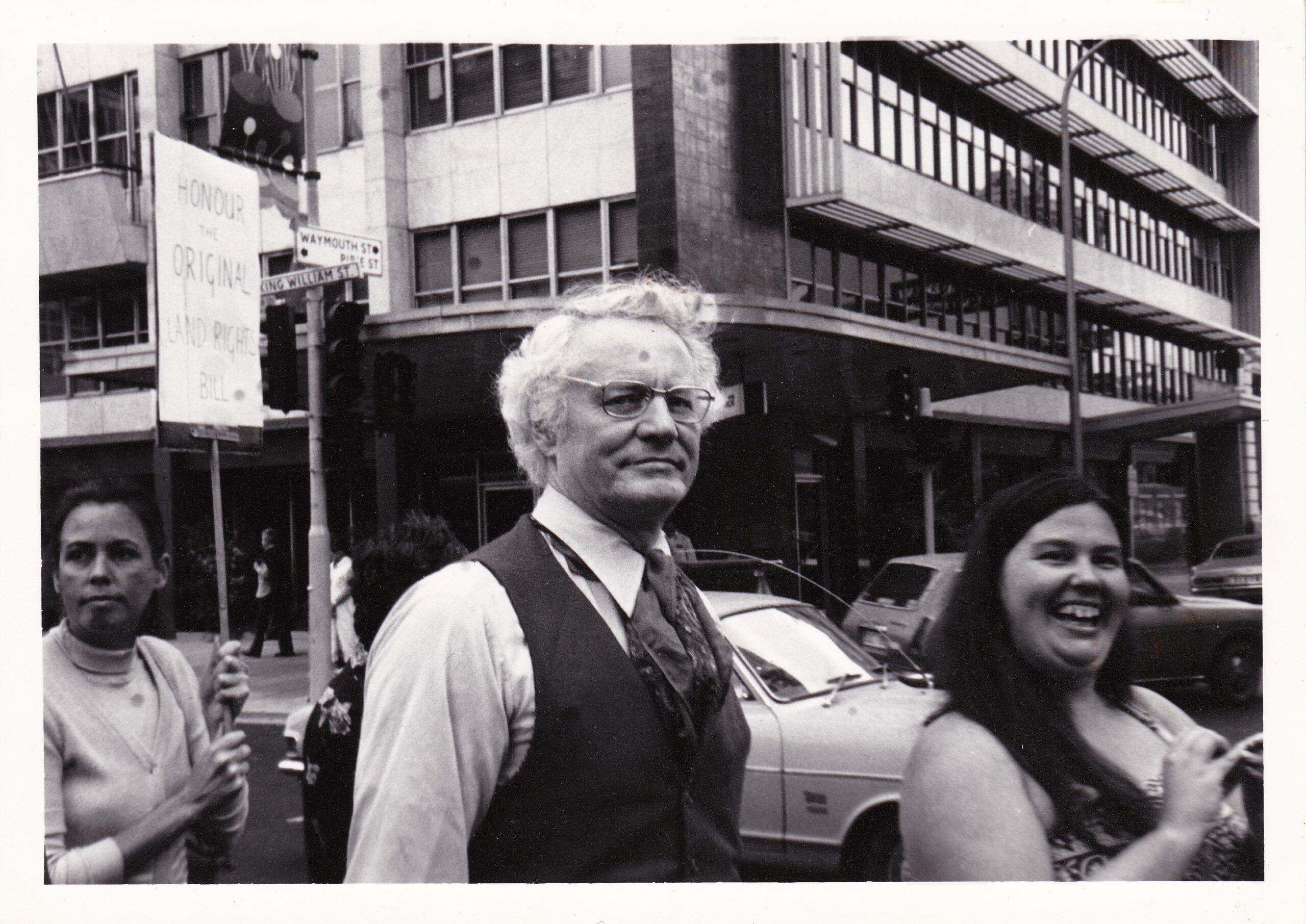

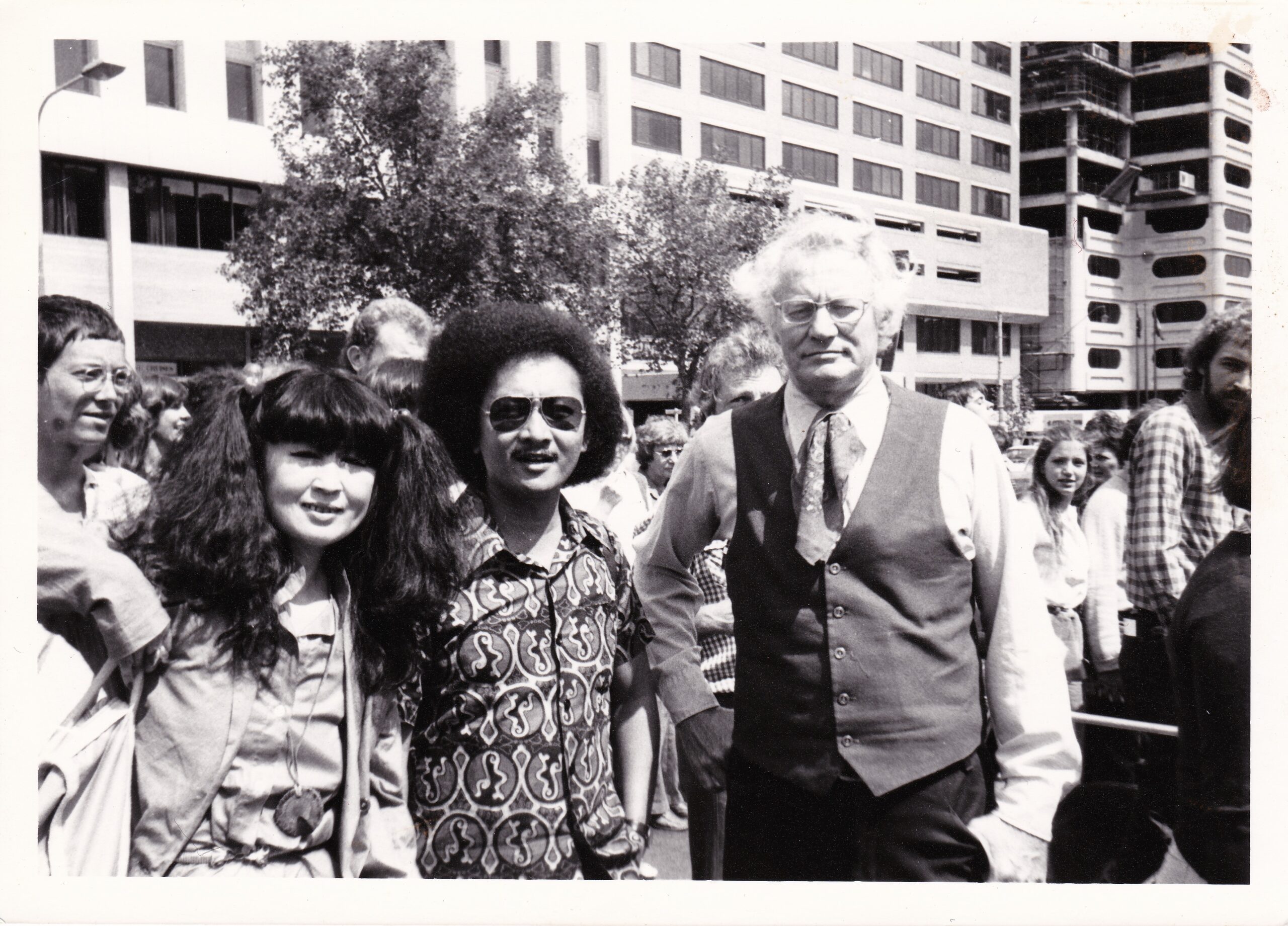

That Saturday, Robert, Darmanto, Kazuko, and I walked arm in arm down King Williams street with several thousand other people, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal. On the outside, just four more people. But to the students from the college and the people from Pitjantjatjara country, it was a sign of international solidarity and a hope that word of their plight and ongoing struggle would somehow reach beyond the conspiracy of silence that enables Europeans to claim an entire continent using the doctrine not of Manifest Destiny, but of “Terra Nullius” – empty, uninhabited, desolate land. From Captain Cook to the King Ranch, from massacres to mining, “until we are given back the land / and the land can make us whole again.”

One day we will all have to make peace with the land and with the indigenous people. Without their help and blessings, no one is going to get very far. It is now many years later and Robert and I have met many times – in Manhattan, Mendocino, Santa Fe, Tesuque Pueblo. I’m still making that walk from the fancy hotel to the Aboriginal college. In an East West Journal interview in 1976, speaking of the book Man-child: A Study of the Infantilization of Man by David Jonas and Doris Kline, Bly states: “The gist of it (the book) is that each generation of Westerners after the Industrial Revolution has been more infantile than the one before. The authors define an adult as someone who can exist in the physical world without a lot of supportive devices. Many Eskimo in old times were probably adults…” If we live in a society “without a father, or models for maturity,” then perhaps the grounded, self-sufficient stance of native peoples such as the Pitjantjatjara, the Lakota, the Ainu, and the Hawaiians can act as the models lacking in technological society. Twenty-five yards or forty thousand years… whichever comes first. There are still people who know how to live here, and by helping them retain the land, we also help ourselves.

Robert, whether you knew it or not, you made a difference in Australia. And you were right about me not belonging in there at Beacon. I belong out here. From the bushes, Happy Birthday.

– John Stokes

Corrales, New Mexico